Careers often unfold over years, but they are usually defined by a handful of moments. For Christian Ramos, one of those moments came on a night in Kauai, when he was working as a travel emergency nurse in a four-bed department at a small critical access hospital.

A man arrived with significant chest pain, consistent with a major heart attack. Christian and his colleagues carried out the level of care a small island hospital could provide, then monitored the patient while they awaited a helicopter and an open bed on Oahu, where he could be transported to a medical center in Honolulu. Standing at that bedside, Christian saw how timely access to specialized care depended not only on what happened in the room, but on a broader chain of logistics and capacity across the region.

“You know the care exists somewhere, but you cannot always get the patient there as quickly as needed,” he says. “That tension, between what is theoretically possible and what is actually available to a patient, has shaped how I think about my work. And that is where GE HealthCare Command Center has contributed to improving visibility into operational factors that influence access to care.”

An education in the emergency room

Christian did not start out with a plan for nursing. Born in Colombia, raised in Aruba and then moving to Texas, he had never given much thought to what might come after high school. A single elective, Introduction to Health Sciences, led him into a certified nursing assistant program and his first job in a rehab center, where nurses encouraged him to pursue additional education and training. He went on to nursing school, rotating through ICU, surgery, pediatrics and obstetrics, but consistently asked to return to the emergency department, drawn to the constant variability and the sense that anything could come through the door.

In Houston, at Memorial Hermann in the Texas Medical Center, he worked in one of the busiest emergency departments in the United States, with high patient volume and a wide mix of trauma, stroke, pediatrics and medical emergencies. ER nursing in such an environment meant ongoing triage, rapid bed turnover, and a frequent need to adjust workflows to accommodate demand. These experiences reinforced for him that access to care depends not only on clinical resources but also on patient flow.

Seeing Queen’s from the inside

When he eventually arrived at The Queen’s Health Systems, Christian saw similar challenges—this time in a geographical setting unlike anywhere else in the country. The Queen’s Health Systems is Hawaii’s largest private nonprofit network and the main referral center for much of the Pacific. The Queen’s Medical Center in downtown Honolulu is a 575-bed acute care facility and the state’s only Level I trauma center.

By the time Christian joined, access to care showed signs of pressure. Observations over a four years period indicated that emergency department boarding at the Honolulu campus had increased by 129 percent. The flagship hospital faced constraints in accepting transfer patients as staff managed care amid staffing and physician shortages and the closure of about 300 community post-acute beds across the islands. Hallways were frequently lined with stretchers, and patients who would otherwise be admitted to dedicated units often remained in the ED due to limited availability upstairs.

In a clinical coach role created for him in the ED, Christian began turning those pressure points into improvement projects. He worked with nurses to streamline workflows, eliminate redundant medication scans, reshape triage routes for suspected COVID patients and retire outdated practices, all aimed at freeing time and resources for the sickest patients.

By 2021, leaders were addressing patient flow at the hospital-wide level, reframing length of stay as an operational and clinical priority, creating a Patient Flow Governance group, standardizing multidisciplinary discharge rounds and introducing a capacity plan with defined surge playbooks. Christian’s scope expanded to include bed control across six hospitals, the regional transfer center, a discharge lounge designed to free up inpatient beds and a new team of patient flow coordinators, shifting them from reactive house supervisors to proactive flow leaders. He also helped launch an escalation line, 691 FLOW, which logged about a thousand calls in its first month and demonstrated the value of a single point for raising discharge and throughput questions.

“You have to connect with your mission. For me, that mission is access—making sure people get the care they need at the right time and in the right place. Command Center gives us better visibility into where operational barriers exist and helps teams address them more quickly.”

Christian Ramos

A new lens on access

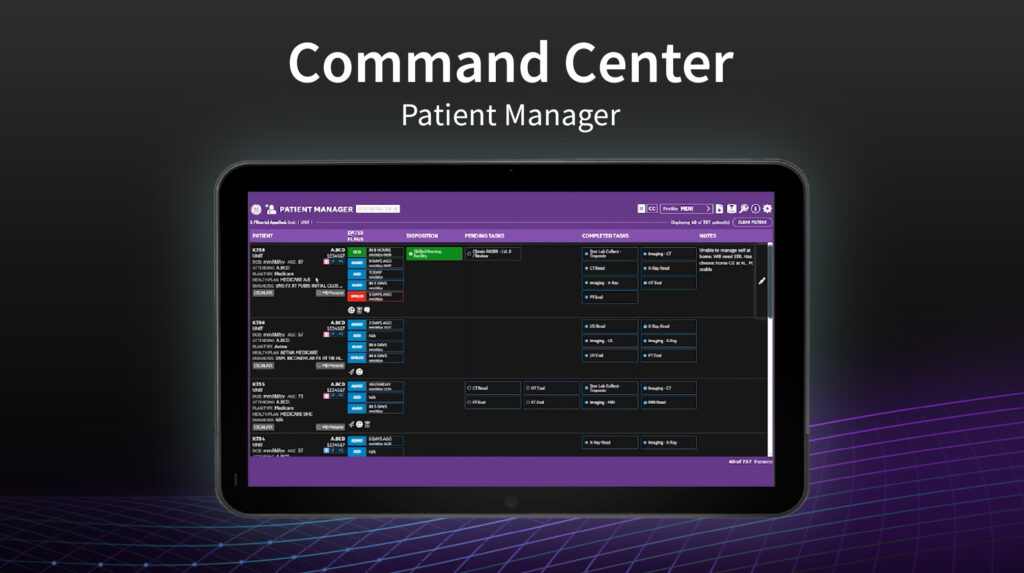

That groundwork created a natural on ramp to more advanced tools. When GE HealthCare Command Center software was implemented at Queen’s, it replaced many manual lists and integrated into the structures already in place, eventually becoming part of a broader physical space.

Command Center is a real-time and predictive operational system that aggregates select data from the electronic health record and other clinical and operational systems. It updates every few seconds and presents the information in tiles that teams use in rounds, huddles and daily decision-making. The software sits above existing systems, connecting operational information related to beds, orders, results and devices, reducing the need for staff to look across multiple screens or spreadsheets.

For Christian and his coordinators, this provides a shared view of system activity. The Patient Manager tile displays each inpatient with an expected discharge date, outstanding tasks and notes from the care team. The Capacity Expediter shows available beds, blocked beds and patients still in the emergency department or recovery areas awaiting placement. Together, these tools consolidate what had been a dispersed set of reports and calls into one visual reference point.

On a typical morning now, a nursing director can open a profile tailored to their unit. It lists only those patients with discharge orders who remain in beds, along with a timer indicating how long they have been waiting. Rather than sending a general hospital-wide report, the director can ask targeted questions about a specific delay, such as waiting for medications or transport. This shifts conversations from broad reminders to specific problem-solving and may, over time, influence culture and workflow.

His team also uses Patient Manager to review trends beyond single delays. One daily report focuses on mobility scores indicating how independently a patient can stand, sit or walk. Patients with higher scores frequently can be discharged home, helping free a bed for someone waiting in the ED or from another island. This supports addressing situations where patients might otherwise be transferred to another facility or remain longer than medically necessary.

Imaging is another area where Command Center supports workflow. Radiology receives many CT, MRI and ultrasound orders each day. Unless a scan is labeled emergent, it may remain in a long queue. Patient Manager allows Christian’s team to identify patients ready for discharge except for pending imaging studies. They share that list with imaging so those exams can be prioritized when appropriate, helping reduce the time patients remain in the ED awaiting placement.

The internal metrics that followed the introduction of Command Center—combined with the governance structures and daily operational practices already in place—suggest improvements in several process areas. Over the first ten months, leaders reported that average length of stay decreased by just over a day, time from ED arrival to inpatient admission decreased by about forty-one percent (a reduction of 248 minutes), ED boarding declined by nearly sixty-four percent, and acceptance of transfer patients increased by more than twenty-two percent. Leaders estimate that year-over-year LOS reductions represented about twenty million dollars in annualized operational savings. These results reflect Queen’s internal data and are specific to their system, processes and context.

A personal mission

For Christian, these changes are most visible in the quieter moments after a helicopter has landed, when a bed is ready and a patient who once might have waited for hours is moved promptly to a unit for further care. The improvements connect directly back to that four-bed ER in Kauai. Every hour shortened in a discharge process and every bed turned over more efficiently increases the likelihood that a patient on another island can be accepted in time.

“It is one thing to attach yourself to a business or a hospital,” he says. “You also have to connect with your mission. For me, that mission is access—making sure people get the care they need at the right time and in the right place. Command Center gives us better visibility into where operational barriers exist and helps teams address them more quickly.”

At the end of a long day, when the helicopter radio is quiet and dashboards show that the emergency department is catching up, he can see how his experiences connect: the teenager in Texas lifting patients in a rehab center, the young nurse in Houston, the travel assignments in Kauai, Big Island and Guam, and his first steps into management. The challenges that once felt overwhelming remain, but they are more visible, more measurable and more open to improvement. For Christian, this aligns with his interest in addressing complex, system-level issues and converting new ideas into meaningful results for the people of Hawaii.