At GE HealthCare, we view responsible AI as a framework that is designed with safety considerations in mind to support patient care, clinical trust, and equitable care. Moving from principles to practice requires clarity on the foundations that guide our work. We organize these into seven pillars of responsible AI in healthcare:

- Safety: We seek to protect against harm to human life, health, property, or the environment associated with unintended applications or access to AI systems.

- Privacy: We strive to implement AI systems in a way that safeguards human autonomy, identity, and dignity with respect to privacy.

- Secure and resilient: We intend to leverage our capabilities to develop and deploy AI systems to withstand unexpected adverse events.

- Accountability and Transparency: We hold ourselves accountable through governance and encourage transparency by sharing of information.

- Fairness: We aim to develop and use AI systems in a way that encourages fairness and increases access to care.

- Explainability and Interpretability: We promote explainability and interpretability of our AI systems and their outputs.

- Validity and reliability: We aim to employ AI systems that produce consistent and accurate outputs.

Together, these pillars set the foundation for how we design and evaluate AI at GE HealthCare. Among them, explainability and interpretability deserve closer attention, as they directly impact how clinicians trust and apply AI in practice.

Explainability vs. interpretability: understanding the critical distinction

In today’s article, part of our ongoing series on responsible AI in healthcare, we focus on explainability and interpretability. First, we will explain the difference between the two concepts. Then we will show how we apply them in practice. While often used interchangeably, these concepts represent distinct yet complementary aspects of AI transparency in healthcare. Interpretability refers to the degree to which a human can understand the internal mechanisms and logic of an AI model.

It’s about comprehending how the model processes information and arrives at its conclusions. In healthcare, interpretability means clinicians can understand the underlying relationships between patient data inputs and AI outputs, enabling them to assess whether the model’s reasoning aligns with established medical knowledge. Explainability, on the other hand, focuses on providing clear, actionable explanations for specific AI decisions or recommendations. While a model may not be fully interpretable in its complexity, it can still be explainable by providing contextual information about why it made a particular recommendation for a specific patient case. The distinction matters profoundly in clinical settings. A radiologist may not need to understand every algorithmic detail of an AI diagnostic tool (full interpretability), but they absolutely need clear explanations of why the AI flagged specific abnormalities in a particular scan (explainability).

Longitudinal patient data

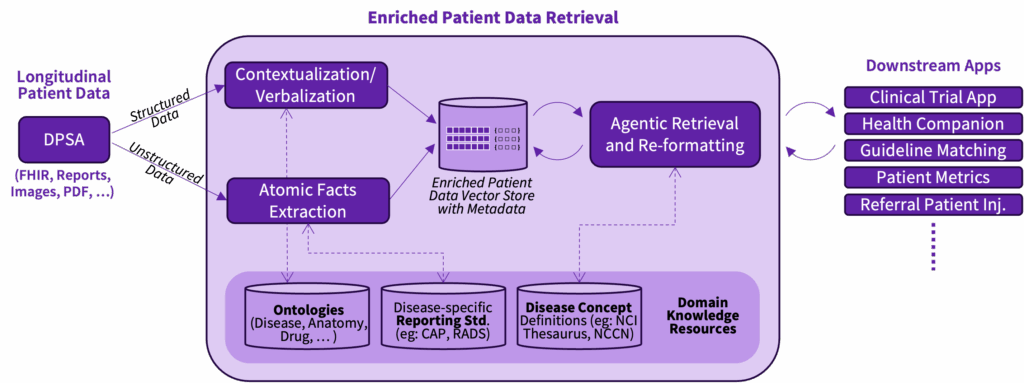

In day-to-day practice, clinicians must navigate massive volumes of longitudinal patient data spread across structured and unstructured sources. Information is captured in lab reports, imaging, physician notes, and external records. Each format has its own vocabulary and level of granularity, making it difficult to synthesize into a coherent clinical picture. This variability not only slows down workflows but also increases the risk of missed context or overlooked details. On top of that, treatment guidelines evolve rapidly. Oncologists, for instance, must track frequent updates in complex protocols.

They need ways to align patient journeys with guidelines while documenting justified deviations. Without intelligent support, this is time-consuming and error-prone. Without the right tools, clinicians spend significant time re-querying systems to extract the same information in different ways. Guideline adherence checks require manual review of patient histories against long, nuanced documents. Even when AI models are applied, if their reasoning is opaque, trust suffers. Clinicians will be hesitant to rely on black-box suggestions when patient care is on the line. At GE HealthCare, we are exploring research on a patient data retrieval service to address this clinical pain point.

From theory to practice

Turning data into actionable insight GE HealthCare’s research on an enriched patient data retrieval service is designed to directly address normalized representations of longitudinal patient data that abstract away variability in input formats while preserving meaning. The enriched patient data retrieval service can recognize medical events like “biochemical recurrence,” which refers to the return of cancer markers after treatment, or treatments such as “LHRH agonists,” drugs used to lower hormone levels in prostate cancer. The service is being applied in research projects such as Project Health Companion (an agentic approach to a virtual tumor board) and CareIntellect for Oncology for clinical trial matching.

By applying disease-aware retrieval agents that are currently exploring research, it could bridge the gap between fine-grained data, such as lab values or treatment codes, and the high-level clinical language that guides decision-making. Instead of leaving these details buried in raw data, the system highlights them in plain clinical language. This could make information easier to find and understand, reduces repeat searching, easing the workload on clinicians. It is being evaluated for potential value in areas like clinical trial matching, applying treatment guidelines, and patient companion tools.

Building on that base, the guideline recommendations system under research could help doctors follow and apply evolving medical guidelines. It could automatically bring in the latest updates, connects live with patient record systems, and organizes guideline text into usable knowledge graphs. In practice, this means an oncologist could potentially see where a patient is in their care journey, why a deviation from standard treatment was made, and what the guidelines suggest next. The system uses methods that break guidelines into smaller chunks and link them to reasoning steps, so its recommendations resemble the way clinicians think. Instead of black-box results, doctors could see clear links between a guideline section, a patient detail, and the suggested action. This clarity has the potential to support trust and confidence in AI-assisted decisions. Enriching these knowledge graphs with ontologies and disease concepts can help facilitate consistency in interpretation, improve usability across diverse clinical contexts, and make the system extensible as new conditions and therapies emerge.

Together, these solutions illustrate how GE HealthCare translates responsible AI principles into practical tools. The research on the enriched patient data retrieval service supports interpretability by structuring and contextualizing raw information, while the guideline recommendations system facilitates explainability through transparent, guideline-based reasoning. Both systems reduce friction in clinical workflows, support clinician trust and confidence in decision-making.

The approach described above demonstrates that responsible AI in healthcare is not a choice between innovation and explainability, but a way to bring both together. By building systems that clinicians can understand, trust, and validate, we ensure that AI supports clinical reasoning rather than replacing it. As healthcare AI continues to evolve, success will come from solutions that support clinical workflows, strengthen professional confidence, and preserve the human touch at the heart of care.