This article written by Dr. Taha Kass-Hout, Global Chief Science and Technology HealthCare originally appeared in Forbes

Imagine a healthcare system where technology enables care providers to spend more time with patients. That would be a marked—and welcomed—change from the reality today.

According to a study from Stanford Medicine, doctors spend 19 minutes with electronic health records (EHRs) for every 12 minutes they spend with a patient. Additionally, seven in 10 physicians report that EHRs have not strengthened their patient relationships, while nearly three-quarters say these systems have increased their daily work hours, contributing to widespread burnout.

That human disconnect isn’t just a side effect of modernization. This represents a fundamental design failure: we’ve built systems that optimize for data, not people. Mid-century modern architecture faced this exact challenge in the mid-1900s—harnessing industrial-scale production while preserving human connection. Architects like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Eero Saarinen created a design language that made massiveness feel intimate and technology feel warm. Today’s healthcare must solve the same paradox.

Design Beyond Aesthetics: Form And Function In Healthcare

One of my most cherished childhood memories is sneaking into my father’s study and pretending to be an architect. My father had an Eames Lounge Chair engineered at a precise 15-degree recline. That angle wasn’t arbitrary. It positioned the sitter to naturally make eye contact with someone across from them, close enough to read facial expressions, angled to invite conversation rather than retreat.

This wasn’t furniture; it was human-centered engineering that optimized interpersonal connection.

An important distinction: mid-century modernism practiced essentialism rather than minimalism—distilling to what works rather than stripping away for aesthetics—a crucial distinction for healthcare design, where we must preserve every element that allows doctors to spend time with patients.

My appreciation for that philosophy deepened over time, especially as I began to notice how the same principles played out at a larger scale while navigating cities, airports and public buildings. When I spent time in New York and Chicago, I saw how mid-century architects took that same ethos of human-centric design and scaled it up. The TWA terminal’s wing-shaped shell guided travelers through a space that flowed without friction or confusion, a rare pleasure in air travel. I came to appreciate how the Seagram Building created a moment of calm by pulling back from Park Avenue, offering a plaza that let people breathe before entering its rhythmically gridded façade.

Simplifying Complexity: Mid-Century Solutions To Modern Problems

After a career as an interventional cardiologist, I believe mid-century architecture principles can help solve some of healthcare’s most complex technological challenges. Three design principles offer a roadmap:

1. Human-Focused Design

The Seagram Building prioritized individual experience within vast spaces through transparent glass façades and open floor plans that maintained human scale.

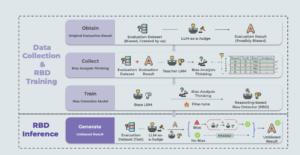

In healthcare, an AI-powered oncology solution that helps enable diagnosis can transform hours of fragmented chart review into minutes by unifying multi-modal patient data from disparate systems into a single view. This approach can empower oncologists to instantly grasp a patient’s complete treatment journey, fundamentally reimagining how cancer care teams navigate complex patient histories.

Like Seagram’s glass walls that revealed rather than concealed, these systems must maintain transparency in their recommendations, augmenting rather than replacing clinical judgment. When technology handles computational complexity in the background, human connection returns to the foreground.

2. Reusable Components

Mid-century modernism revolutionized architecture through modular design. The Seagram Building’s 27.5-foot structural bays and standardized bronze mullions could be manufactured off-site and assembled into countless configurations. This created elegance through repetition while allowing evolution.

Healthcare technology needs this same modularity. Today’s medical software resembles pre-modern architecture: every system is bespoke and incompatible. The solution lies in reusable digital components—standardized data models, common authentication systems and interoperable interfaces.

Just as architects combined standard steel beams into unique structures, healthcare developers should assemble proven components into new applications. Clinicians encounter familiar interfaces across systems while developers focus on innovation rather than reinventing the basics.

3. Accessible Design

Mid-century designers achieved accessibility through mass production. Look at the molded plywood chairs manufactured at scale, modular building systems and simple materials like concrete and steel that created spaces without ornamental expense. That spirit must guide healthcare innovation, and there are encouraging signs when it comes to advancing accessible care.

I’ve seen this in practice with tools like GE HealthCare’s Vscan Air, a pocket-sized ultrasound that puts hospital-grade imaging in the hands of community clinics—even in remote areas. Paired with software that guides users step by step through cardiac scans, it aims to turn specialized expertise into skills accessible to everyday health professionals.

Today, AI-powered clinical decision support systems can distill complex patient histories into clear treatment suggestions, supporting physician judgment. Healthcare data standards enable modular development by allowing systems to share components like patient records.

I see steps like these as healthcare’s molded plywood moment—democratizing access through design.

Beyond The Hospital Walls: Infusing Accessibility And Flexibility

Critics sometimes dismiss mid-century modernism for its lack of uniqueness and emphasis on industrial design, but its deeper legacy is the framework of systemic thinking. Light, structure, circulation, proportionality and economics were never isolated concerns. They were parts of a single equation whose goal was to maximize human well-being. Healthcare today needs that same integrative rigor.

The city builders of the 1950s solved their scale problem with steel, glass and concrete. Ours will be solved with data, algorithms and bandwidth, but only if we inherit the same conviction that design must serve everyone. Mid-century architecture taught us that a single detail, repeated with care, can dignify millions of lives. Let’s apply that lesson so the next generation of doctors spends less time scrolling and more time meeting the gaze of the people they heal.

The transformation begins with a simple question: Does this design bring us closer together or push us further apart? Whether you’re a healthcare executive evaluating new technology, an engineer building the next clinical system or a patient navigating care, demand environments that honor human connection. The blueprints exist. The principles are proven. Now we must build.